Why I Failed with the Apple III and Steve Jobs Succeeded With the Macintosh

You hear a lot about Steve Jobs from second-hand accounts. But I knew Steve better than most — because he was my colleague.

We both worked at Apple in the 1980s when it spun out some products that brought new life to the brand. That’s because some of the most innovative minds — including Trip Hawkins (Founder of Electronic Arts), Taylor Pullman (Inventor of Filemaker), and Rob Campbell (Inventor of PowerPoint) — worked there as well. They also preceded me as the Apple III Group Product Managers.

There was an incredible amount of talent at Apple in the 80s. So, it is no surprise that a lot of motivational stories have emerged from this time period.

But let me tell you a different story. This is a story about failure. It’s the story of a product that slipped through organizational cracks — and what I learned from the experience.

Apple recruited me to bring the first hard disk drive on a PC to market. My job was to lead product management and strategy for the Apple III — a personal computer aimed at business professionals. The Apple III was supposed to solve the pain points of the Apple II and put our brand back on the map for business.

Instead, the Apple III was discontinued four years after its initial launch — the same year that Jobs introduced Macintosh to the world and began another period of rapid growth at Apple.

It was painful to watch the Apple III fail. But it taught me a valuable lesson: even the most exciting products will fail without complete organizational support.

Here are the lessons I learned about why the Apple III product didn’t last longer — while Macintosh survived and later thrived. The story might have ended differently if we were able to:

Agree on vision The first challenge was that everyone at Apple had a different vision for the organization’s future. And Steve Jobs didn’t want any other product positioned in the market that might interfere with “his” Macintosh. Not only did he want the Apple III out of the marketplace — he failed to acknowledge that profits from the Apple III and Apple II computers were giving him the resources to develop, build, market, and sell the Macintosh.

Part of the problem at that time was an explicit company strategy to promote and position Apple as “two young Steves running around in Birkenstocks with $100 bills falling out of their pockets.” This was the positioning statement that Apple’s first investor and former Head of Intel Marketing wrote in his company marketing strategy memo. Funny, but true. And it meant there was little extra space for a non-Steve creation.

There was a total lack of unity around the Apple III from the start. And that led to its downfall. The Apple III was only seen internally as a “slightly improved” Apple II. That internal mindset impacted the Apple III’s market performance.

Set aside politics The lack of agreement on vision created an environment that was confrontational. Apple at that time was split into two distinct camps. One supported the Macintosh; the other supported the Apple III.

This is me at Apple’s annual sales meeting at the Hilton Hawaiian Villiage Hotel in Waikiki. I didn’t have Steve’s $1M to promote his Macintosh to the worldwide Sales team at the October 1983 convention. So, my Marketing Communications Manager bought little Apple III stickers, and we stuck them on everyone’s shirts.

I bought a Samurai jacket and sword, then made rounds on the dinner’s last night to personally remind each salesperson that they should start selling Apple IIIs when they got home. After all, the Mac would not be shipping for at least four more months. Steve Jobs, on the other hand, was going around telling everyone that the Apple III was losing lots of money — completely invalidating the work that I was doing.

Understand market segmentation When I took over the Apple III product line, the first thing I did was speak with the product’s architect, Jef Raskin (who, by the way, also designed the Macintosh). He described the markets he had in mind for the Apple III as SOHO (Small Office, Home Office) and SMB (Small and Medium Business).

He also said that throughout the five years when he worked on the Apple III, I was the first person to come talk with him about market segmentation. That proves how insular different departments at Apple were.

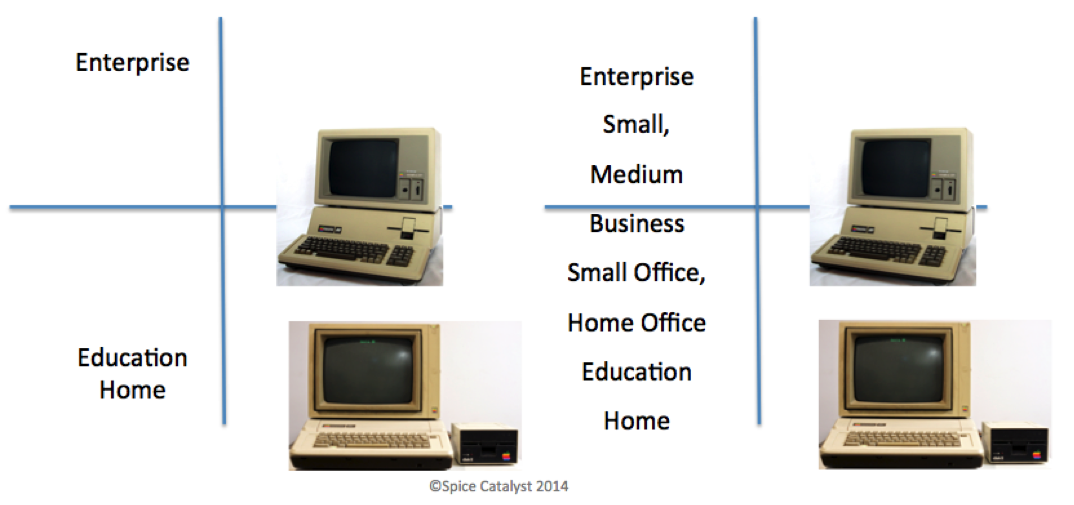

To make matters worse, Marketing did not agree that there was any demand for the Apple III in the SOHO or SMB market. That’s because Market Analysts had not identified such market segments yet. So, Apple’s own Marketing team could not identify those as market segments by themselves. And since everyone argued internally about whether Apple was an Enterprise or SMB company, attempts to define the Apple III’s market segments were drowned out by the noise of continued discussions about the product’s larger vision.

Apple’s Marketing department continued to waver between the home, education, and enterprise markets, as shown above.

Ultimately, the greatest challenge was that Steve Jobs did not like selling to three different personas — the user, the business influencer, and the actual IT buyer — which are found in the enterprise market. He did not like selling to the IT department since it preferred cheap PCs and didn’t care about user experience. Most crucially, he thought the business market — which the Apple III was designed for — should be the sole marketplace for his beloved Macintosh.

Nail the positioning Because Apple couldn’t get the Apple III’s market segmentation right, we also misfired on positioning. The Richards Group — the Dallas ad agency I hired — helped me position the product as “Apple III Means Business.” Steve Hayden, my copywriter who went on to author Apple’s infamous 1984 commercial, supported this positioning. But Apple’s Corporate Marketing team did not. They were too stuck on their goal to position the III as the Apple II’s slightly enhanced big brother.

That’s because the rest of the organization was actively focused on positioning the Macintosh — not the Apple III. An engineer told Jobs and John Sculley at a company meeting that they would not succeed in positioning the Macintosh as a “business” computer because it did not have two floppy drives and could only run a 10k program, amongst other limitations.

I vividly remember Sculley’s response: “We will market with mirrors.” I have always wondered if that was a Pepsi thing since he was the former President of Pepsi America who was credited for taking on Coke with the “Pepsi Challenge.”

Regardless, the mirrors didn’t reflect much. And that beloved business market caught on to the Mac’s limitations. After 100,000 units sold (mostly to developers) in 1984, sales dropped to just four units in January 1985. The Apple III remained an afterthought throughout this whole process.

Measure meaningful KPIs KPIs are a benchmark that organizations use to predict future success. And once the product team agrees on them, they should be freely circulated throughout the larger organization. So, when Apple’s Manufacturing division used the wrong metrics to measure the Apple III — and did not share those metrics with our Product team and organization — it set the Apple III up for failure.

Del Yocam — VP of Manufacturing and future Apple President — said my Apple IIIs were messing up his manufacturing floor in Dallas. He had to make 40,000 Apple IIs per month — and “the lousy 3,000 Apple IIIs” I was forecasting to sell each month were getting in his way. Clearly, his metric — or key performance indicator (KPI) — was “units sold.” In perfect 20/20 hindsight, this was the wrong KPI for the Apple III.

Instead, we should have focused on profitability. I ran the numbers and found that the Apple III product line was contributing over $100M per year in gross profits. That’s because the Apple III focused on the Enterprise market and had a much higher Average Selling Price (ASP) than the Apple II. Hardly a failure. But we were not measuring Average Selling Price — which proved to be a fatal mistake.

So, ask yourself: “What are the unintended consequences of lacking complete organizational alignment?”

The consequence of what I’ve described is that I shut the Apple III product line down due to lack of company support. And because of the mistakes discussed above, about 1,500 A+ Apple employees were forced to seek new careers elsewhere.

With the right perspective, sometimes we can learn more from our failures than from our achievements. Ultimately, no product can survive if its team is not on the same page – no matter how talented that team is.

This is a guest post by David Fradin. If you are looking to be a great product manager or owner, create brilliant strategy, and build visual product roadmaps — start a free trial of Aha!

David is a Silicon Valley veteran. He was a Product Manager for Hewlett Packard’s first office systems products in the 80s and later managed over 500 products in the Apple III division while Steve Jobs oversaw the Macintosh division. David has conducted product management and product marketing management training for companies including Capital One Bank, Cisco, Infosys, and Pitney Bowes. Today, he is Principal at Spice Catalyst, where he leads product management and marketing courses. He also teaches in-person planning workshops that cover the entire Product Management lifecycle. David can also be found on Twitter @DavidFradin1.